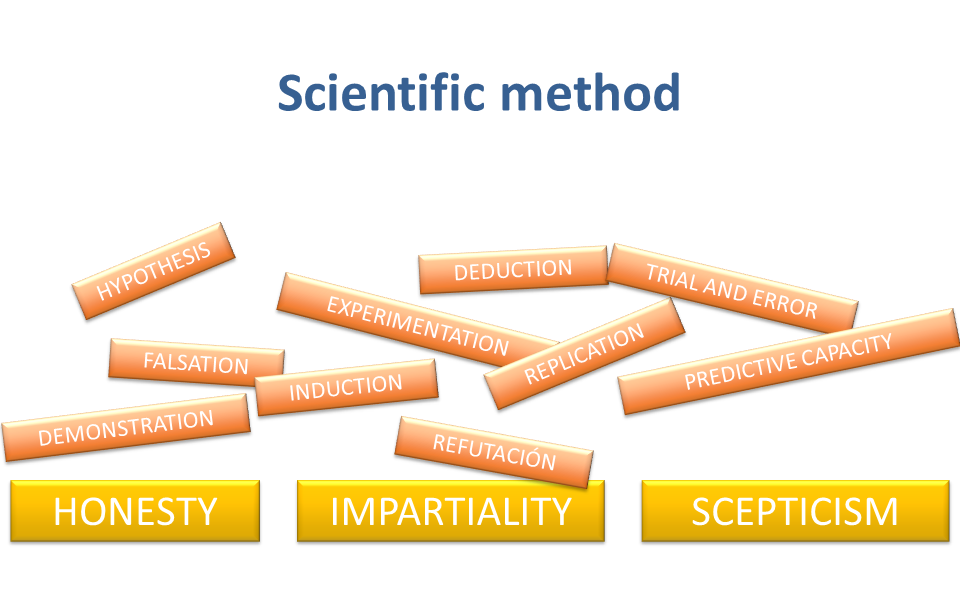

Which are the foundations of the scientific method? In relation to the scientific method, a series of concepts are handled such as: hypothesis, test, falseness, demonstration, evidence, induction, deduction, experiment, “trial and error”, refutation, predictive capacity, replication, etc.

First of all, it is worth clarifying what we mean by the scientific word when speaking of scientific method. It is a word that at least reminds me of the image of Albert Einstein writing on a blackboard or Marie Curie handling glass tubes, scales and microscopes.

It is important to distinguish between a professional scientist and a methodological scientist. Perhaps we can strictly say that a scientist is one who acts according to the “scientific method”, regardless of his profession, but the reality is that the word “scientist” is used with multiple meanings. At least:

- Professional scientist.

- Methodological scientist.

- Supported by evidence, and therefore, credible.

For example, it can be said that a hypothesis is “scientific” for different reasons:

- It has been proposed by a professional scientist.

- It is part of a research project guided by the scientific method.

- The hypothesis is supported by at least some evidence and therefore, is plausible.

“Scientific” can also mean “reliable, good, correct,” for example, if we say that induction and deduction are scientific (or more scientific) knowledge-gathering tools than dream interpretation and intuition. “Scientific” is also used as a synonym for “measurable” or “quantifiable” for example, when it is said, perhaps erroneously, that the study of subjective experiences –sentience, consciousness, pleasure and suffering– is not scientific (or it is unscientific, or it’s more philosophical than scientific), since these (subjective experiences) cannot be measured.

It is interesting to note that to define the scientific method is not doing science, but rather to do philosophy (philosophy of science); and that trying to use the scientific method to determine what the scientific method is does not seem like an easy path.

Although there are different opinions about which or what are the scientific methods, in any case, there are some things that we can say about the scientific method that are not only widely supported and accepted; they are so evident and fundamental that we can take them for granted.

A fundamental aspect of science compared to other ways of obtaining knowledge is the recognition of ignorance, in a permanent methodological skepticism that always takes into account the possibility of being wrong (both others and ourselves). It is assumed that science does not establish absolute certainties. Instead, science makes claims supported by evidence. We could call these statements provisional truths. Humility is key in the scientific method. True scientists should always be willing to acknowledge mistakes and change their minds in the face of new and better evidence.

Science also offers explanations, connecting events and justifying the reasons for their claims. The most probable theories along with the best evidence produce the most probable conclusions. But the scientific attitude must always be alert to change its mind in the event of emerging new evidence or new theories that are more reasonable than the previous ones. When professional scientists do not behave like this, they are ceasing to be methodological scientists.

By reductio ad absurdum we could also say that the scientific method cannot consist of lying, favoritism and being naïve. If a professional scientist hides the unfavorable results of his experiments, and only recognizes the results favorable to his theory, we would not say he is being honest or scientific. Those who only listen carefully to those arguments in favor of their ideology, ignoring the arguments and evidence against it will be proving to have an unjustified, anti-scientific favoritism. And if someone believes in anything, without demanding evidence or explanations, they will be credulous, which does not seem to correspond to a scientific attitude either.

As a result of the foregoing, I believe that the method and the scientific attitude are supported by three basic ideas: honesty, impartiality and skepticism.

Imagine a research team testing a new drug in a group of ten patients, of whom six die, two improve and two remain stable. He repeats the experiment with ten other patients and in this case only four die, and all the rest remain stable. Repeat the experiment a third time and they all die. He repeats the experiment a fourth time, with ten other new patients, and this time none dies, seven of them improve and three remain stable.

The team then decides to discard the first three experiments and publish only the results of the fourth experiment, announcing a 70% effectiveness and no side effects. Of course, the report will be written in beautiful scientific jargon, with abundant references, charts, and all the scientific marketing we are used to.

It is evident that, in this case, the investigation team would be being dishonest. Although the report of the study of the last ten cases, taken in isolation, can be considered scrupulously scientific, in reality it is not. The activity can be described, maybe, as “scientific” from a professional point of view, but not from a methodological point of view. The example that I have described is obviously an exaggeration and a caricature, and there are various controls that prevent these situations, but it would be naive to think that this type of thing never happens.

These reflections are particularly suitable to approach the issue of sentience, since, although we are not going to be able to use many of the tools of the scientific method, we can tackle this problem by being strictly rigorous in their foundations: honesty, impartiality and skepticism.

My own view is that Science is a method wherein we seek to understand our universe (existence) in a way that poses the least or no contradictions, in other words self-consistant. The epistemological method called science itself has evolved thus as opposed to other epistemological methods. So ‘no contradiction’ is the bootstrap as well as main principle subsumed in the method. This has to be so because there is no gold standard ‘apriori’. We just don’t know certainty. We have to derive our own gold standard fully consistant from beginning to end. Our moral theory also should be subsumed in this process and it is a matter of time before a formal consistant deterministic moral theory will be formulated and seamlessly integrated into science. Since all Science is underpinned by Physics which is itself underpinned by some magical Lagrangian, the moral Lagrangian is waiting to be formulated.