“The problem is that the story of life is always told by the living and the survivors… They are the ones who write the script, and they affirm that everything is worth it… But what about the silenced voices, the forgotten or unknown faces, and those who never even had a say in all of this? Huh? What would happen to that baby, who was born only to die moments after birth from a respiratory complication, or that other one who died barely a year and half after she was born because her alcoholic father beat her to death, or that little boy whose mother decided on his freedom and got rid of him by faking a drowning getting away with it, what do you have to say about it? That 20-something-year-old girl who was kidnapped, raped and cut into eight pieces like a chicken, whose killer was never caught? That medieval teenager who contracted dysentery or typhus or leprosy and died a horribly disgusting bloody, dirty and totally painful way? All those inconscious cows and pigs and deer whose high point in life is ending up in a supermarket display or on someone’s plate?”

— Reddit, Anonymous.

If we want to do the greatest good, we must take into account intense suffering

The movement known as Effective Altruism has created a very interesting intellectual framework to explore how to do the greatest good in the world, based on rationality and evidence. Or, in other words, using scientific or, if preferred, business criteria in altruistic projects (a good introduction here). At first glance, this may seem trivial or insulting. Did organizations behave irrationally and deny the evidence before Effective Altruism? Didn’t they pretend to be effective? The truth is that altruism has often been based on deontology and character ethics (and within it, for example, virtue ethics) and not on consequentialism (here more info). Some argue that Effective Altruism is not necessarily consequentialist (some interesting references are this and this). But Effective Altruism is based on results. If what they mean is that many effective altruists are not consequentialists, but deontologists or virtuous, perhaps they are so because this is, for them, the best way to be effective and achieve the best consequences.

In the world there are many problems. If we want to work personally to help solve them, there are several keys to keep in mind. Ideally, at a career crossroads, I should try to work on something that 1) I like 2) I’m good at 3) Is in demand (I get paid for it) and 4) Contributes to a better world (see 80,000 hour guides). But what happens when I want something resolved, but I’m not thinking of working on it myself, but I’m considering making a financial donation so that others can do it? The criteria for determining which are the organizations or projects that most effectively address the problem of doing the greatest good in the world have certain similarities with the previous ones. To assess the most effective destination of my donation, I must take into account the needs or problems that exist, the capacities and shortcomings of the organizations that try to solve them, the probability of success and the difference that my donation makes in this scheme of things. In other words, the analysis must take into account factors such as 1) The importance or seriousness of that specific cause or problem that we want to solve, prevent or alleviate 2) The expected impact in case of success of the project or initiative (which could be included together in the previous point, although it seems clearer to separate them) 3) the probability of success or ease of obtaining positive results (or “tractability”) 4) the “neglectedness”, roughly equivalent to the financing needs of such organization or project and 5) the ability of the project to absorb our donation effectively. This last point will not be relevant if the donations I intend to make are small. But if our donation capacity is great, and given that for every project and organization and for every moment of every project and organization there must be an optimal organizational size and funding (or several, but definitely not all sizes or all funding are optimal), our donation could be excessive and would be better used in a combined way in several initiatives. For more information, you can consult this page.

As stated, Effective Altruism is based on results. It is not enough to donate to the organization that needs it most or to those who work to alleviate the most tragic situations. There is the sad possibility that the effectiveness of the actions against a certain problem will be low or even null, if the problem is very complex and difficult to solve (also, by the way, the impact can be negative). To make results-based decisions, we need data. Numbers. Quantifying is usually a good idea, although we are going to run into serious problems when making measurements. In particular, we have a big problem getting reliable numbers when we enter the horrible world of intense suffering.

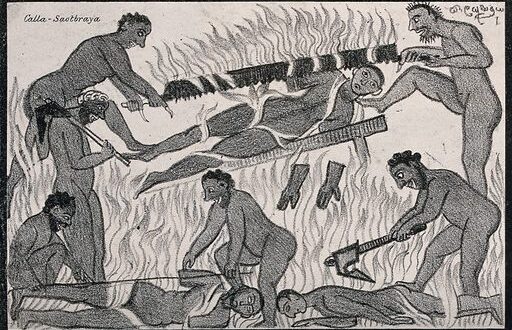

Subjective experiences like pain and suffering are very difficult to measure. One solution is to use surveys in which the protagonists of the suffering describe it, adjusting it on a scale; or comparatively, taking two situations and specifying which is worse. The problem is that there is suffering that is very difficult or impossible to survey. This is the case of suffering in non-human animals, very young humans, humans in oppressive situations, humans with some cognitive impairment, and humans who do not survive the experience of suffering, or for any other reason they cannot communicate it. For example, suffering in fetuses, newborns and small kids, suffering in girls and woman in cultures where they are almost properties, suffering in young boys in some complicated family environments, rape in small kids (not easy to survey), people being tortured and then killed, individuals with cognitive impairment or dementia (not easy to survey), individuals dying without palliative care, who die drowned, starved to death, die burned, due to hypothermia, etc.

How to quantify the effectiveness of initiatives aimed at alleviating and preventing intense suffering in such a way that it is possible to compare and determine which are the most effective altruistic actions?

The first thing we need to include intense suffering in the calculations of effectiveness of altruistic projects is to have the intention and the ability to do so. There are things that are instinctively rejected by perception, such as excrement or rot. Something similar can happen with intense suffering. Empathy can be painful, and being aware of and delving into the existence of intense suffering can be very unpleasant, very painful, depressing, so it is possible that our mind reacts by ignoring it, rejecting it, impulsively dismissing its importance, as a defense mechanism, in the same way that talking about death is taboo in many circumstances. It will not help if we find ourselves in a social environment where these taboos are respected. On the other hand, perhaps the reason for refusing to include intense suffering in the calculations of effectiveness of altruistic projects is not determined by the biases and taboos of the researchers, but of the donors. That is to say, if the main donor of my altruistic project does not even want to hear about intense suffering, it will be very difficult for us to take it into account in our project.

Second, since we want to include the alleviation and prevention of intense suffering in the calculations of effectiveness of various altruistic projects, under a criterion of effective altruism we should not simply abandon the idea as soon as we realize how difficult it is to measure it precisely. Once we know that something exists and that it is significant to our project (intense suffering is relevant by definition, at least at the dimension of the intensity of the experience), we must take it into account one way or another. As mentioned in “The Tyranny of Metrics“, metrics can be distorted by measuring the most easily measurable. We don’t want to make that mistake. At this point we have two options: try to achieve metrics related to intense suffering or abandon the idea due to its extreme difficulty. In this second case, it would be fair to clearly recognize it when we talk about it, for example, saying, “According to the results of our study, these projects and initiatives would be the most effective for improving well-being, given that the study is limited to population X, and population Y has not been considered,” and we could add some methodological explanation such as, “This is because our study is based on surveying the main subjects, and in many cases this survey is not possible.”

Finally, if we insist on quantifying the effectiveness of the relief and prevention of intense suffering so that we can make a better and more complete comparison of the effectiveness of altruistic projects with them, how can we do it in cases in which we cannot survey the protagonist of said intense suffering? From an effective altruism approach, we not only have to be able to assign numerical value to the disvalue of negative experiences, but also numerically assess the ability of projects to prevent them.

Here are some ideas:

- Survey experts, family and the general public about their quantitative assessment of the different negative experiences. These questions can be asked with numerical scales or in a comparative way, for example, asking: If you had to choose between suffering ten years of mild depression or the experience of burning 50% of your body with second degree burns, what would you choose? If you had to choose between being raped by a stranger or having your finger amputated, which would you choose?

- Make forensic use of stress markers (in corpses), such as beta-endorphins and cortisol.

- Establish correlations between media campaigns and the prevention of torture, murder and executions for political reasons.

- Establish correlations between sociopolitical factors (such as income level, education) and crime.

- Establish correlations between family planning capacity (contraceptive training, access to pregnancy prevention mechanisms, access to abortion) of one generation in a certain geographic area and the crime rate of the next generation.

Acknowledgments

- Thanks to Hegesias de Cirene for the anonymous headline quote

- Thanks Michael D. Plant whose works motivated me to write this.

1 Comment