Speciesism is a moral preference that discriminates (positively or negatively) beings of certain species by the simple fact of belonging to that species, without taking into account other circumstances. In my opinion, there are many errors and misunderstandings associated with the idea of speciesism:

Error 1: Speciesism is the preference of the human species by the human species.

The most clear and widespread speciesism is positive and arbitrary discrimination of human beings towards other human beings, just for the fact of being humans[1]. However, this is not the only case. Humans can also positively discriminate dogs, cats, parrots, dolphins, elephants or ladybugs; And negatively wolves, lions, wild boars, cockroaches, rats and pigeons, just because they have the (good or bad) luck to belong to this species, without taking into account other conditions.

Error 2: There is only one type of speciesism.

There are many ways to be a speciesist. Some human cultures have a positive speciesist preference for cats, dogs or cows, but other cultures do not, or even discriminate dogs.

Error 3: Only humans can be speciesist.

I believe that, for example, great apes and dogs are not not only passive moral subjects (rights holders) but also moral agents, able to make moral judgments and have speciesist preferences. When I say that great apes are moral agents, I am not saying that great apes are moral agents in the same way as an average adult human. Consider the following: Newborn human infants are not moral agents, but human infants are, long before the legal age of majority, which is usually established between the ages of 14 and 21, depending on the legislation. Evidently, there is no significant change in the moral capacity of a human child at the instant when he reaches the age of majority. The ability to establish moral judgments does not seem to be binary but rather gradual. This ability is not only determined by age, but is affected by various circumstances such as drugs, physical injuries, psychological impacts, neurodegenerative diseases… Human children can have this moral capacity. Other mammals as well.

Error 4: The opposite of speciesism is the consideration of all animals equally (there is only one type of non-speciesism).

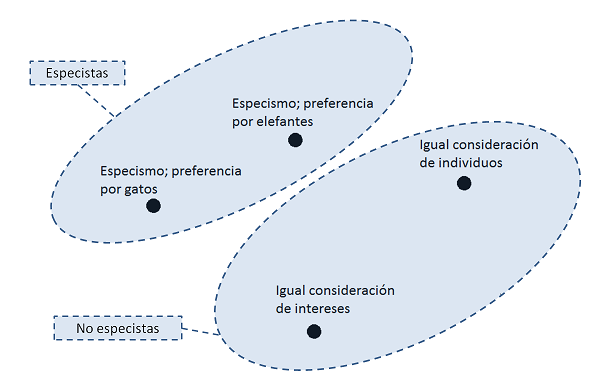

Sometimes it is thought that the speciesism has a unique opposite, the anti-speciesism, and that that unique opposite consists in considering all the animals equally. But speciesism has no contrary, but many contraries. Not only are there many ways to be a speciesist, but there are also many ways to be anti-speciesist. And these forms are complex: it is not a line with two extremes: speciesism and anti-speciesism; But rather of a plane, or even a multidimensional space, with many points. One way to be non-speciesist is to consider all animals equally, but another way of being non-speciesist is to consider all interests equally.

Error 5: The systematic preference for an animal of a species against another animal of another species is always speciesist.

Speciesism is the moral preference that discriminates by the mere fact of belonging to a species. One way to avoid being speciesist is to consider all interests equally regardless of the species. This does not mean that in the face of moral problems there is a greater (or lesser) habitual consideration to animals of certain species than by others of different species.

Faced with moral problems, it is possible to have preference for an animal of one species against another of another, without being speciesist. Moral problems like these:

- A chicken and an elephant are in danger, and I can only save one of them.

- A dog with intestinal worms will become sick if the parasites continue to develop in your body.

Let someone think that a particular elephant is a more sensitive, intelligent and social being than a particular chicken; Or even that someone thinks that an average adult elephant is probably a more sensitive, intelligent and social being than an average adult chicken, and that if both are in danger, show a greater preference for saving one against another, it is not speciesist

I call them “moral problems” and not “moral dilemmas” because it is understood that dilemmas have only two possible solutions, when there are usually several options against a moral problem.

In this article, in the quote: «I’m what Jon Bockman might call a “species-ist.” I think elephants—sweet, sensitive, and social creatures that they are—should count for more than chickens do.» anti-speciesism is erroneously understood as the consideration of all animals equally, when that is only a theoretical type of anti-speciesism, of which I do not think there are real cases.

Reasoning about the example of the dog with worms can scare many people. Most of us would decide to kill the worms and save the dog. But why do we do it, why do we prefer the dog? Is it a moral intuition? Is it a learned behavior? Do we follow social norms, perhaps religious? Is it dangerous to reason about such things? Is it more dangerous to reason than not? Do we do it because the interests of the dog are greater than the interests of all worms? Do we do it because the earthworms are disgusting and are also a threat to ourselves? Do we do it because we love the dog and feel identified with it, while we can not do the same with the worms?

Another example: Many people are disgusted by cockroaches and rats or are terrified by snakes and scorpions. These aversions may have an evolutionary origin related to the possible transmission of diseases or poisons, in the same way that dogs hate the mushrooms. These cases may not be speciesism, since although all individuals of a species are generally discriminated against, this discrimination may not be realized by belonging to the species, but for other reasons. For example who kills cockroaches but saves ladybugs may be impressed by the beauty of the colors of the second. In that case it would not be discriminating by species but by beauty or aesthetics: it could save the life of a rare and beautiful iridescent cockroach. Many people hate rats, brown or black, but they love white hamsters.

Conclusions

Many preferences for particular individuals may not be speciesists. On the other hand, they are the moral or legal rules, deontological, which can be speciesists. It would be fairer if these moral or legal rules evolved to have greater precision in the consideration of individuals and their interests, without giving as much importance to the species to which they belong. For example, a dead individual has no interest, belongs to the species that belongs.

Recommended Links:

[1] Of course, there is nothing to criticize when one individual has moral consideration for another, for example, when a white man has moral consideration for another white man. We have the moral problem when the white man omits moral consideration for another individual, simply because he is black (racism), or because he is a woman (sexism). Speciesism is another arbitrary discrimination that uses the concept of species instead of sex or skin color as a discriminatory argument.

1 Comment