Summary of asymmetries between good and bad (relative to sentient beings as we know them)

- There are more laws that punish than laws that reward. There are no shortage of reasons for this.

- Typically, the news is bad news. There are good ones, but they must be few, or not so important.

- Finding yourself in most places in the universe will make you suffer and kill you (most places in the universe are either too cold or too hot).

- It takes 20 years to build a reputation. Only five minutes to destroy it.

- A reversal of fortune can ruin a lifetime of peace and happiness in one minute. But an occasional stroke of good luck is not enough to compensate for a lifetime of trouble and misery.

- It is very rare to find the equivalent of a traumatic experience, but in a positive way.

- Causing pain is easier than causing pleasure. Doing evil is easier than doing good. Destroying is easier than building.

- It is easier to reduce the pleasant effect of a typically pleasant experience than to reduce the painful aspect of a typically unpleasant experience.

- Without a doubt, at certain times it is best to do nothing, not move. But systematic inaction precedes pain and death. If you don’t do anything, if you stay where you are, if you don’t take care of your body, it will degrade, making you suffer until you die. To experience pleasure you have to do something. To experience pain it is enough to do nothing.

- There is much more pain than pleasure (in intensity, duration and number of occurrences).

In this text I try to answer two very related questions: “Is there a symmetry between suffering and enjoyment?” and “Can suffering be compensated with enjoyment?”

Investigating the way in which we respond to these questions is very relevant, since we may have biases or blindness that are encouraging to make bad decisions, such as the survivorship bias. By better understanding and evaluating suffering and enjoyment we can more easily minimize suffering and maximize enjoyment, as well as compensate for bad experiences, if such a thing were possible.

In what follows I will use the words “pleasure” and “enjoyment” as synonyms (of positive experiences), in the same way that “pain” and “suffering” will mean the same thing (negative experiences). The differences between physical and psychic pleasure; and physical and psychic pain, are not considered relevant here.

Are pleasure and pain values of a single axis? How many axes of experience are there?

It is common to mentally represent pleasure and pain respectively with positive and negative values of the same axis (a single dimension). While this metaphor has some meaning and descriptive value, in other respects it is wrong.

To complete it, we can say that pleasure and pain are also in a way like sugar and salt. Sugar and salt are flavors that we could describe as “opposites” and that, however, can exist at the same time. That is, we should talk about two axes (with positive values), not just one (with positive and negative values).

Although we are accustomed to our experiences being both positive and negative, we could imagine a world or a type of sentient being for which only negative experiences existed, or much more interesting, that only positive experiences existed, as proposed by David Pearce in his “gradients of bliss“.

We can also imagine worlds or beings for which all experiences were neutral, and even, forcing a little imagination, worlds or beings that do not have two, but three or more types of experiences, which correspond to three or more axes.

Is there a symmetry between pleasure and pain?

Pleasure and pain are intuitively symmetrical in the sense of being contrary: we seek the former, but we try to avoid the latter. But in some aspects we can find lack of symmetry. The following are some cases of lack of symmetry between pleasure and pain.

1.- Different cost or difficulty (probably related to entropy and the second law of thermodynamics)

If a sentient living being that we know well (animals) were to move to any randomly chosen place in the universe, it would probably suffer intensely and die (quickly, but sadly, not instantly).

Provoking pain is easier than provoking pleasure. We sentient beings need to feed ourselves and adapt constantly to the environment. In general, if we minimize our activity, for example, if we remain motionless, pain ensues (from hunger, thirst, cold, heat …). This happens except in very specific situations where it is best to remain motionless, such as a bear hibernating in winter. Instead, to get pleasure (and above all, to avoid pain), we must expressly do something (except for rare cases).

In short, pain comes effortlessly, but to get pleasure we must work for it. I think the evidence of this asymmetry is very large.

If we represent pleasure and pain through positive and negative values of the same axis (in a single dimension), with pleasure on the right and pain on the left, it seems that:

- We will always be interested in moving to the right

- If we do not do anything, our experiences probably move to the left

- In general, it will cost us an effort (energy, resources) to move to the right

- In short, it is as if the ground moves under our feet, and we have to walk continuously to be in the same place. This would be an extended version of the hedonic treadmill concept.

[Text box: “Symmetries between pleasure and pain”]

Although this text focuses on defending the existence of asymmetries. It is fair to mention the symmetries, even though they are considered obvious.

- We seek pleasure and stay away from pain (although we can argue that we are much more dedicated to the latter than the former)

- We can simulate both joy and sadness, both pleasure and pain.

- Revelation or enlightenment type experiences, although much less frequent than traumatic ones, can transform the individual in a certain positive and permanent way.

- There are traumatic experiences and revelatory experiences (although the former are much more common)

- There is a certain equivalent of the hedonic treadmill in terms of suffering, at least in some cases. A slight discomfort that becomes chronic becomes acceptable and can even be ignored (for example, being a little cold and having wet feet for hours). Not only that, but if it is suddenly relieved (we arrive somewhere warm and dry), then it is interpreted as pleasure. Which would not have happened if we had not been in that state of discomfort first. In any case, the symmetry does not seem very strong, and the degree of adaptation to positive experiences seems very high, almost absolute, while the degree of adaptation to negative experiences seems low. Mild chronic pain can be ignored most of the time, but it seems to leave some after-effects such as constant mild depression.

- Some modern currents of psychology and pedagogy claim that rewards work just as well or even better than punishment. Depending on how we frame and exemplify this, it will be true. But overall, I don’t think so.

- We can “negotiate” with ourselves exchanges of pleasure and pain in both directions (accepting a pain to obtain a pleasure, or rejecting a pleasure to avoid a pain) although as I will argue later, all of these exchanges can be interpreted as having as their objective, ultimately, and even if in a complex way, reduce suffering.

[/text box]

2.- Different amount

In my opinion, another asymmetry that exists between pleasure and pain is that in practice there is much more pain than pleasure.

To say that there is “more” pain than pleasure (or vice versa) can mean several things: do we refer to the number of cases? Or do we also consider the intensity of the experiences? And its duration?

If we want to quantify experiences, whether positive or negative, it is very reasonable to take into account these three parameters or dimensions in which the experiences unfold, which are their intensity, their duration and the number of occurrences.

- Intensity: There seems to be a known limit to pleasure, difficult to overcome, and yet the pain seems to be much deeper and potentially much deeper. The most pleasurable experiences we have ever known can make us “lose our heads” but rarely lose our judgment, while painful experiences are unsettling, leading to mental deterioration, insanity and death. Of course, this may change in the future.

- Duration: The very painful experiences are longer and their negative effects lengthen more in time, than the very pleasant experiences, whose positive effects fade with greater speed. As Eduardo Mendoza said in the mouth of one of his novel characters (I quote from memory because I do not find the literal quotation, but the idea is faithful): it is frustrating to see how a stroke of good luck is not enough to make up for a lifetime of discomfort and misery; and yet a setback of fortune can ruin a lifetime of happiness in a minute.

- Number of occurrences: I believe that at any moment there are more suffering individuals than enjoying individuals. This is probably the most controversial point.

3.- Different motivation

I believe that we are much more motivated to avoid suffering than to achieve pleasure, and that many of the things that at first we seem to do for pleasure can be explained by a desire to avoid pain. In addition, I believe that, of all the possible ways to compensate for experiences, the most usual by far is to accept a small suffering to avoid greater suffering. All this I explain in greater detail in the next section.

Can suffering be compensated with pleasure?

When we talk about the possibility of compensating a pain with a pleasure, obviously we are not saying that one annuls the other in the sense of ceasing to exist, but in the sense that the overall result “is positive”, it is something “good” (or better than another result) and it seems like a good decision to make.

Regarding this type of “compensation”, I think there is something we do continuously, which is to accept a little suffering in order to avoid greater suffering. This preference has its symmetric, which is to refuse a small pleasure if in return we can obtain a greater pleasure. I think the opportunity for this second situation to occur is much less frequent, and this represents another asymmetry between pleasure and pain.

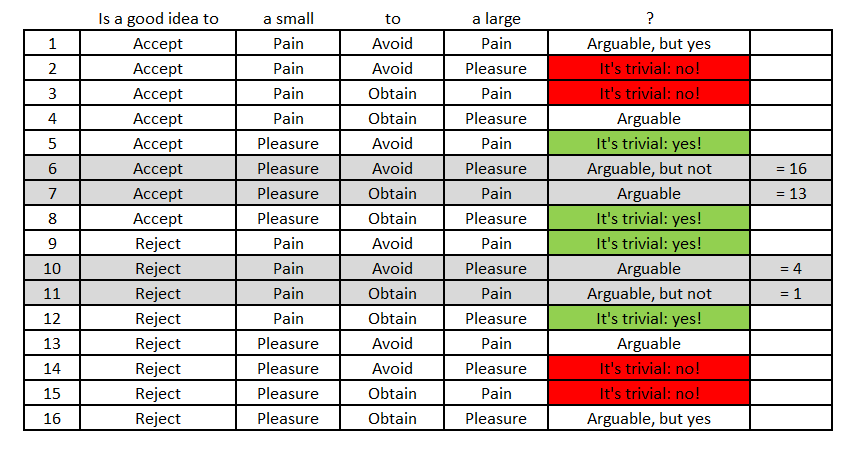

In relation to these “compensations” there are four possibilities that are interesting to investigate, which I will number as “1”, “4”, “13” and “16”. Actually, there are more options, but many of them are trivial or are equivalent to others. At the end of the text, I detail all the combinations. The four main possibilities are:

- Accept a small pain in order to avoid a big pain

- Accept a small pain in order to obtain a great pleasure

- Refuse a small pleasure in order to avoid a big pain

- Refuse a small pleasure with the goal of obtaining a great pleasure

They can be expressed in the form of a question:

- Would you accept a small pain whose consequence would be to avoid a big pain?

- Would you accept a small pain whose consequence would be to obtain a great pleasure?

- Would you refuse a small pleasure whose consequence would be to avoid a big pain?

- Would you refuse a small pleasure whose consequence was to obtain a great pleasure?

Defining these categories of possibilities to explore through questions is very intuitive and direct, but it can also be confusing or imprecise. It does not really matter much if we answer “Yes” or “No” to these questions, but instead, on the one hand, identify that possibility, and on the other, know what we should answer or answer if we had all the necessary information, that is, try to determine what the answer should be if what we intend is to maximize happiness and minimize suffering, whether in a single individual under selfish criteria; or in several individuals, if what we seek is, in some way, to maximize the common good.

A table with all the combinations

The following table represents all the combinations related to “Accept” or “Reject” an experience (either Painful or Pleasant) with the aim of Avoiding or Obtaining a greater experience, either Painful or Pleasant.

Other asymmetries or clues about asymmetries and between good and bad experiences

- It seems easier to voluntarily provoke the transition to a state of sadness than to a state of joy. Of course, except for the actors who have to simulate tears, hardly anyone has an interest in achieving the former, while the latter is generally sought and desired. The asymmetry is that, at least apparently, if we put the same efforts in forcing sadness as in forcing joy, it seems that the former would be easier to achieve.

- “In most societies and within most ethical customs, people do not feel ethically obligated to give others joy but they do feel ethically obligated to avoid causing others harm. The court of law operates in this manner too. You can’t sue someone for not giving you a birthday present but you can sue somebody for damaging your property or being violent towards you, etc.” —Alexander Bratchuli

- The “Survivorship Bias” reinforces the false believe that there’s no so much intense suffering in the world. The origin of this false believe is that we can’t survey humans that do not survive the experience of (intense) suffering. See this post by Janique Behman.

- Magnus Vinding covers the subject of symmetries and compensations between pleasure and pain in his response to this article (1,2 and 3) of Zach Groff.

- “A person only capable of suffering would desire non-existence. But a person only capable of happiness wouldn’t desire existence. Even in the face of imminent demise he will just remain blissfully happy.” —@abisjajo

- Injury vs healing: “It can take less of a second to tear a major ligament whereas to heal it will take months of physiotherapy, possibly surgery and always the chance it will never heal properly.” —@CarlosCardosoAN

- Asymmetry between creating suffering vs. happiness: it’s wrong to create suffering but not wrong to fail to create happiness. By Jeff McMahan calls. Melinda A. Roberts and others have defended this asymmetry. David Benatar highlights this argument. Cited by Brian Tomasik.

Summary

As a summary of the ideas presented here, I believe suffering abounds and not enjoyment, and that suffering can hardly be compensated with pleasure. I think that most of the time (or even every time), when we believe that we accept a little suffering to achieve greater pleasure later (or before), in reality what we are doing mainly is to accept a little suffering to avoid greater suffering. For example:

- We do not eat just for pleasure, but to prevent hunger. The fundamental thing about a meal is to calm hunger.

- We do not have sex solely for pleasure, but to avoid the pain caused by the frustration of unresolved sexual tension.

- We do not look for a companion just for being happy together, but also for not being sad and lonely.

- We do not go on vacation once a year to a distant country only to enjoy new experiences, exotic foods and paradisiacal places, but to avoid the boredom and frustration of staying in the usual city, always doing the same.

In my opinion, the reason for this is that pain and suffering are very relevant, while pleasure and happiness are not.

Other asymmetries

- When singing, it is much easier to give low notes than high notes

- When investing, it is easier to buy low than sell high. That is, it is easier to correctly estimate that a value is low (and therefore, that it is going to go up or at least not go down much more) than to correctly estimate that a value is high (and therefore, that it is going to go down or at least it won’t go up much more)

- Things go up more likely than they go down. Celestial bodies tend to have the geometric shape of the sphere.

It is easier to break an egg than to create an egg.

Counter-examples

- The heat makes things rise.

- Chickens turn corn kernels into eggs. The corn plant converts sun, soil and water into corn kernels.

Valuation and estimation

- Initial phase of the universe: all inert matter, maximum entropy

- Ascending phase of pain, development of life. Part of her discovers how to avoid suffering.

- Maximum pain, balance between inert matter and living matter (some suffer, some do not)

- Descending phase of pain, life without suffering occupies more and more niches

- Final phase of the universe: all matter is living matter without suffering

Another asymmetry between good and bad

https://twitter.com/josh_c_jackson/status/1597283877168775168

>> The word for good is similar in English (“good”) German (“gut”) and Faroese (“góðan”). But the word for bad is “bad” in English, “schlecht” in German, and “illur” in Faroese. In new research, we show that this is a broader pattern that we call “valence-dependent mutation”