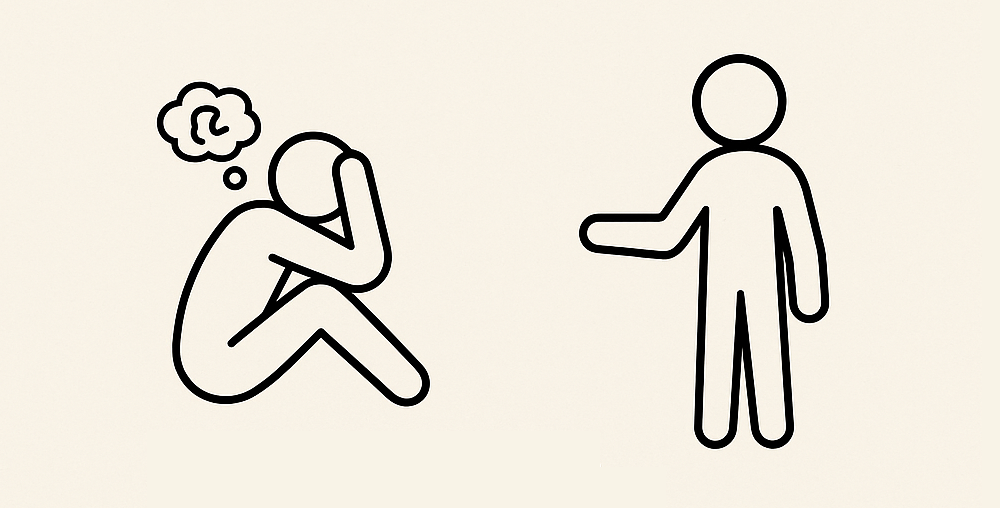

“Those who most need help are often in the worst position to ask for it properly.”

This principle—which we might call the paradox of helping—reveals a deep structural problem in mutual support systems: suffering not only generates a need for help, but also impairs the capacities necessary to express that need in an appropriate or socially acceptable way.

- Emotional, cognitive, or social dysfunction doesn’t just create need; it also sabotages the ability to signal that need effectively or in socially acceptable ways.

- Demanding rational, polite, or coherent behavior as a prerequisite for assistance risks excluding exactly those who need it most.

- Waiting for someone to “ask correctly” is already a failure of the support system. Effective aid requires proactive identification and engagement.

- If institutions respond more to the form of a request than to the depth of need, resources may flow to the most skilled performers of need rather than to the genuinely vulnerable.

I’ve kept this principle in mind every time I’ve witnessed a conflict between two people. Those who most need your help and understanding are probably those who make the most communication errors. My own mistakes, flaws, and weaknesses have allowed me to understand this.

The paradox manifests itself in multiple areas:

- Psychological: A person with depression may isolate themselves, feel unworthy of support, or lack the energy to ask for it.

- Educational: The student who most needs guidance may be precisely the one who least requests it or even the one who most rejects it.

- Healthcare: A patient with extreme anxiety, psychosis, or mood disorders may resist treatment or be unable to clearly describe their symptoms.

- Economic: People living in structural poverty often lack the time, resources, or knowledge to access programs designed to help them.

On a more abstract level, we could say it’s a form of functional entropy: when an individual or a system—be it psychological, social, or institutional—enters into crisis, its capacity for self-healing is also impaired. Need and inability become intertwined.

This has important implications:

- Help must be proactive. Waiting for someone to “correctly ask” for help is already a failure of the system. Effective help requires early detection and a proactive attitude.

- Help should not be conditional on good behavior. If we require that those who need help act rationally, politely, or coherently as a condition for providing it, we are excluding precisely those who need it most.

- There is a risk of perverse incentives. If institutions respond more to the form of the request than to the depth of the need, resources may end up going to those who best pretend they need help, not to those who truly need it.

Of course, this doesn’t only apply to communication. Every time we do wrong, it’s because we have a problem. If we shout with hatred, it’s because we feel unwell. If we attack, it’s out of fear or dissatisfaction. All aggressors, murderers, torturers, and rapists are also, in a way, victims, but in this case, victims of the absurd machine of madness and pain that is nature, filtered through selective pressure. Fortunately, we are in a position to change this if we want.