The traditional division between left and right has long been the dominant axis in ideological cartography. However, this dichotomy has proven over time to be not only insufficient but even misleading. The categories of “left” and “right” have lost any clear correspondence with the actual positions of citizens, parties, and governments. Their common use—in media, debates, and analysis—often oversimplifies complex and multifaceted positions, serving more as emotional or historical labels than as analytical tools.

In response to this inadequacy, the Nolan Chart represented a significant advance. Proposed by David Nolan in the 1970s, the chart added a second dimension to the left-right axis (in the progressive-conservative sense), incorporating a vertical axis that ranges from authoritarianism to libertarianism. This allowed for more accurate representation of individuals who, for example, support free-market economics while rejecting social conservatism, or those who promote equality without necessarily endorsing strong state control.

However, even this two-dimensional model remains limited. There are psychological and epistemological factors that lie beyond these two axes, especially regarding how individuals interpret power, human nature, and the function of politics.

Furthermore, the term “authoritarianism” appears biased due to its negative connotation, leaning in favor of libertarianism. I believe it is more honest to rewrite the Nolan diagram using the most positive—or at least neutral—terms possible. For that reason, instead of the usual “authoritarianism,” I propose “intelligent planning”.

Proposal: A Third Dimension — Idealism vs. Skepticism

I propose adding a third dimension to the diagram—one that represents not specific political stances but meta-stances, and in particular, the cognitive and moral attitude toward power and human agency. This third axis would range from idealism to skepticism:

-

On the idealistic end, we find those who tend to trust their political representatives, support “their” party or leader even while in power, and believe that it is both possible and desirable to build a just society through the right decisions made from positions of authority.

-

On the skeptical end, we find those who deeply distrust power, maintain that individuals—no matter how noble their initial intentions—tend to become corrupted upon gaining influence, and who therefore vote with a logic of containment: not for the one they most support, but for the one likely to do the least harm. This attitude results in systematic criticism even of the party they sympathize with.

This dimension does not intend to establish a moral hierarchy between idealism and skepticism. Both extremes have risks and virtues. Idealism can lead to naivety and personality cults but also fosters commitment and hope. Skepticism may be lucid and protective but can also veer into cynicism or paralysis.

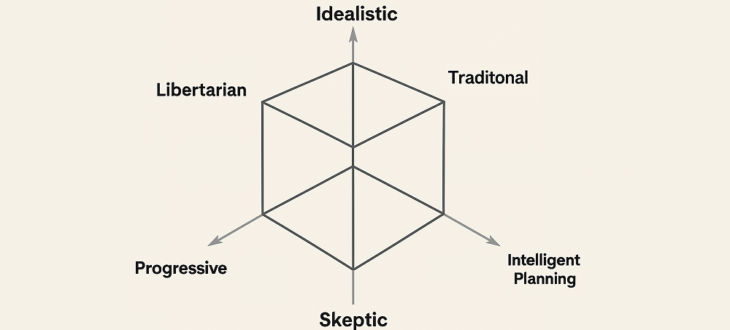

An Ideological Cube

By incorporating this third dimension, the classic Nolan diagram becomes a three-dimensional ideological cube, in which each individual can be located within a conceptual space defined by three axes:

-

X-Axis: Progressive–Innovative vs. Conservative–Protective

(Exploration of alternatives vs. Application of time-tested solutions) -

Y-Axis: Intelligent Planning vs. Libertarianism

(State control and economic intervention vs. Individual autonomy and free market) -

Z-Axis: Idealism vs. Skepticism

(Trust vs. distrust in power and human nature)

This model not only allows for greater precision but also helps illuminate certain nuanced political behaviors—some of which may seem paradoxical but become intelligible in this 3D framework:

-

Idealists who support innovative authoritarian policies “for the common good”

-

Statists demanding increased government intervention while distrusting all government

-

Progressive skeptics who doubt human goodness yet advocate for dismantling police and military forces

-

Pragmatic conservatives who fear power excesses, even from their own side

Background and Similar Proposals

The idea of a three-dimensional model of political ideology is not new. Among the comparable proposals are:

-

Hans Eysenck, who in the 1950s proposed a two-axis model: one related to radicalism-conservatism, and the other to authoritarianism-libertarianism. Although he did not envision a cube, he anticipated the need for more than one axis.

-

Mitchell’s Political Compass 3D, a three-dimensional version of the well-known “Political Compass,” which adds an axis representing attitudes toward change: progressive vs. traditionalist, or modernist vs. conservative.

-

More recently, researchers like Jonathan Haidt have proposed complex psychological models (such as the Moral Foundations Theory) to map the underlying values that guide political positions—though these are not always visualized as a cube.

Nevertheless, the idealism–skepticism axis remains relatively unexplored as a visual dimension in political mapping. And yet, it is crucial. It reflects something that institutional politics rarely acknowledges: that what matters is not only what we believe, but how we hold, defend, and question those beliefs.

Conclusion: Thinking in Cubes

Thinking in cubes may seem more difficult than thinking in lines or planes, but it also offers a richer and more realistic way of understanding politics. We are not just innovators or conservatives. Nor are we merely statists or libertarians. We are also—and perhaps most importantly—more or less skeptical about power and human nature. And that is, without doubt, an axis worth not ignoring.

In this text I have made every effort to give a positive categorization to the political ideas in which I do not believe.

I have been invited as a speaker at a roundtable in the libertarian field and one of the ideas I want to propose is to refer to the opposing positions in terms as positive as possible.

On other occasions when I have made a similar point, I have been criticized for being condescending, for being a kind of double-agent who maximizes kindness toward the other party to showcase his own virtue as an argument to defend his position. I think it’s a very pertinent criticism.