“I teach one thing and one thing only: suffering and the end of suffering” –Gautama Buddha

Imagine a world where everybody is happy (satisfied) and there are no negative experiences.

In this world, to be jealous (jealousy as we know it now) will be impossible, because jealousy is a negative experience. In this world, some people will be happy, and others even happier, but nobody really cares how much. I think this is a good argument in favor of negative utilitarianism, that is, that reducing suffering is morally relevant, but increasing happiness is not morally relevant.

In this imaginary world, even if increasing happiness is a good thing, it’s not morally relevant. Because it is not relevant at all.

Increasing happiness (when the happiness level is already above zero) is not relevant by definition. To increase happiness is “good”, but is not “relevant”. Why? If someone is over the zero, really over the zero, with absolutely no negative experience (like being jealous of other’s happiness), by definition that being is already happy and for that being to be more happy is… well… yeah, is “good” but it’s not relevant at all. It’s very difficult for us to imagine it, maybe because we never have been in that state or even because we didn’t ever know anybody that has reached that state. But we can try to imagine someone very calmed, without fear, completely relaxed and satisfied with present, past and future. We can imagine that person receiving good news, one after another, or enjoying some pleasures, some good and other better. At any moment that person will be satisfied. Already happy, in a way that being happier is not a big deal.

If being happier is really a concern, we’re not being happy at all: we are being frustrated. Real happiness has to include some kind of “tranquility” (“tranquilism”) [1] in which we prefer to stay better, and probably we don’t have anything better to do than being happier, but we don’t really need to be better, so being better it’s good, but it’s not relevant.

Therefore, in my opinion, whenever there is suffering, there will be a motivation to avoid suffering. But once suffering has been avoided in all possible dimensions, the motivation to increase enjoyment is minimal, if not nonexistent.

Look at the photo that heads this article. If you had limited resources and could only help the child on the left (to increase their happiness) or the child on the right (to reduce their suffering), which of the two would you help? How many happier times should we be able to make the children satisfied like the one on the left, so that it is worth ignoring the needs of the children who suffer like the one on the right? Is there such a number?

The conclussion is that we must focus on reducing intense suffering.

Some examples

We all have the experience of willingly enduring some suffering, because of the rewards we hope it brings us. I agree with that, that’s a valid description of what’s happening, and even is how I’d describe it in common language or when I’m not very conscious about the topic, just skimming what’s happening.

But when I go deeper in my analysis about whats happening, I discover that I accept a suffering X to get the Y pleasure (or reward) because I have a model of myself in which if I don’t get Y or at least, if I don’t fight to get Y, I will suffer Z being Z greater than X. For instance:

- I’m going to work hard tonight, which is painful, to get more money, with which I can give myself some pleasures, but it will also help me pay the rent for the apartment or medical treatment if things go wrong. This example is simple, let’s go with another less intuitive one.

- I’m going to work hard tonight, which is painful, to get more articles published, or more songs recorded, to get a better social status and recognition, which at first sight sounds nice, but deep down I’m doing it because I being able to get that recognition and not getting it would be more painful than working hard to get it. That is to say, the mental model that I have of myself having some abilities (intellectual, musical, whatever…) and not using them is that of someone depressed, sorry for having wasted their life instead of having shone for their talents. only in exchange for a few sleepless nights.

- I drive 500 km on Friday to see my girlfriend. It sure will be nice to be with her on Saturday. But staying home all alone without her for the weekend would be more painful than driving 7 hours. When you love your girl but being without her for a few days isn’t painful at all, you don’t spend a whole day driving to see her. You just wait a few days.

- You don’t have intentionally a son to enjoy being father, even if you will enjoy that, but because you are obsessed with having children and you feel incomplete without that. There’s no good time to have children, they will absorb your time, energy and money. But some people have the mental model that being without them will be worst. People who want a family just to enjoy it usually say maybe next year, every year, because they don’t need children, because they don’t suffer being without them.

Negative utilitarianism in a single individual: the multiple dimensions argument

To me, negative utilitarianism is not just a normative ethical theory, but a response to the world as it really is. For example, here some wonder about how many ice creams are needed to equal the value of a life. But I do not think that people buy ice creams to enjoy, but they do (or they should) to prevent suffering, to be “above zero”.

In my opinion, to be far above zero is just a precaution people take to prevent to be below zero. To have a margin of safety. Or to try to alleviate the suffering in some other dimension of their existence.

When someone is below zero in just one dimension (sex, money, frienship, health…) and above in the others, they will divert all necessary resources from the other positive indicators to the negative indicator, trying to be above zero in all of them. If they dont (if they keep trying to increase one positive indicator while others remain negative) it will end very very bad. Negative Utilitarianism works in just one individual (with the different indicators) as the normative moral theory of Negative Utilitarianism works with several individuals: the priority is to be above zero (or at least zero), in each possible dimension (if we speak of a single individual), or in each individual (if we speak of several individuals).

The distinction between the “good”, the “better” and the “relevant”

I use the adjective “relevant” in the same meaning that Jonathan Leighton uses the word “urgency” in expressions like “there is nothing else that has greater urgency than preventing or relieving the intense suffering of sentient beings” [2] or “the most urgent issue in our world [is] the intense suffering of sentient beings” [3].

I will give an example to try to clarify the nuances between the expressions “good”, “better” and “relevant”, both in relation to negative experiences, as well as positive ones.

When publishing a book, a double space between words is considered is a typo (which can be very difficult to detect). If in the days next to the date in which we have committed to publish the book we found this errata, we would correct it. This is good, and the book will be better without that mistake. But it will hardly be relevant. There are, on the contrary, really serious misprints that can change the meaning of what we wanted to say in the book, in addition to other tasks that are much more important to deal with and that can also fail, such as the promotion and distribution of the book, or the translation to other languages.

Once published, we will be probably awaiting feedback from readers. Although it hurts, we should accept the possibility that some reader does not like the book. It would be terrible to have many readers and that all the criticisms were bad, or many of them. Instead, it would be really great to have many readers, many critics of the book, and most of it good. And, although it is difficult to imagine, if absolutely all the criticisms were good… Wow! That would be wonderful!

In this case, each new positive review of the book would be good, and it would be better to find another new reader who has also liked the book. But the really relevant thing would not be to have one more positive recommendation, nor the exact words with which the book is valued positively, but the fact that people always like it.

In this metaphor, the errata is equivalent to a slight suffering, a speck of dust in the eye. Eliminating or preventing this mild suffering is good, and the world would be better without it. But it is not relevant, it is not urgent. There are much more important things to do. The good reception of the book corresponds with the positive experiences. If all the experiences are positive, it is not very relevant if there are more or less, or if they are very intense or not so intense. The important thing is that all of them are positive.

Towards a mathematical definition of relevance

It might be useful to have a precise definition of the concept of “relevance”. It could also not be because, although the definition is strict, it may not accurately reflect what we wanted to say. But we can try it.

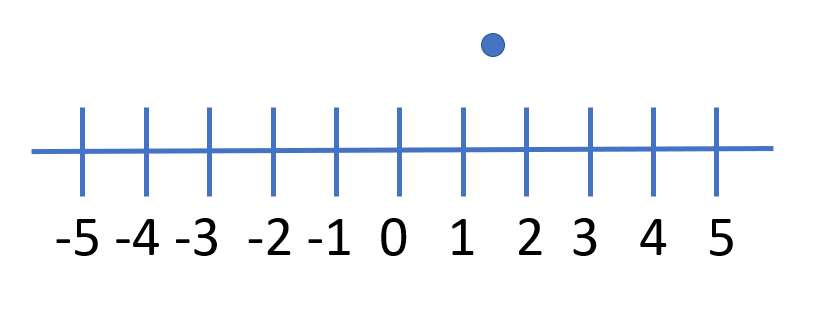

A simple way to do it is to establish a graph of a single axis, with positive and negative values, that represents our welfare state, thinking for example of an only being that wants to be as happy as possible. Of course, this selfish restriction may not represent reality. In addition, we must remember that there may be several experiences both negative and positive at the same time and in several areas, so it would clearly not be enough with an axis, but it is a way to start.

In this representation, any value to the right of another is better than the one on your left and therefore it is good to move from one state to another that is more right.

To define relevant we could take into account how much we are willing to invest or risk to improve our current state. The relevance of a state could be defined as the cost or risk that we are willing to assume to modify it. In general, when the probability of success is high, we will try to improve our state, and if we consider it low, we will take the precaution of not trying to improve our state. But this will not be the only criterion. If we are rational, we will risk more the less we have to lose, and instead we will ensure our state when it is good enough. Because of this, we can consider the relevance of a state as the inverse value of the probability of success that we consider minimally acceptable to run the risk of trying to improve that state. If our current situation is bad, we will be willing to take the risk to improve it, but if it is very good, it might not be rational to take the risk of trying to improve it even more.

For example, in the case of the double-space error, it is good to correct this error, but its relevance is so low that the probability of success must be very high, practically 100%. We would never accept that, for trying to correct the error of double space, we run the risk of, for example, that the printer confuse the versions and put in print a very old version.

Negative utilitarianism and sex

I am going to set an example that does not necessarily have to work for all people, but I think it can illustrate negative utilitarianism in the matter of sex and love for many.

Think of a couple in love. If this couple never makes love, it is very possible that this causes frustration. This does not necessarily have to happen in all couples. There are couples who never have sex and are happy. But let’s assume it happens, in this example.

Let’s keep thinking about the same couple. If you do it once a month, you may be motivated to do it more frequently because of the suffering that an unfulfilled desire entails over too long. Suppose now that the couple makes love once a week and that they are satisfied with this. There is no frustration for either. Maybe one or even both would prefer to make love two or three times a week, even every day, but this would not be really important, because are making love once a week, and for them that’s fine.

Of course, the frequency from which frustration disappears is very personal and depends on many circumstances, but such frequency exists. For some, making love once a year, or at least once in a lifetime, may be the most they can imagine aspiring to. For others, everything that is not making love every day or even three times a day is a frustrated desire, an unease. But there is always this frequency limit, which of course change over time for each individual for different reasons.

The important point is that once this frequency is exceeded, the individual is well and does not need more. But if it is not overcome, there is frustration and therefore suffering. And ultimately what motivates therefore to make love is that suffering. Not the positive experience. Once the limit frequency is exceeded, of course you can make love again, and you will enjoy it, and making love twice is better than doing it only once. But if there is no frustration, it really does not feel necessary to do it that second time, and if it is not done, it’s ok.

In short, below the limit frequency, the motivation to make love is frustration. Above the limit frequency there is really no motivation to make love. Of course, there may be brains motivated to have the more orgasms the better, without end, like rats that die pressing a lever that activates their reward centers. Brains can work in many ways. What I think negative utilitarianism says is that, in general, brains are motivated to avoid as much suffering as possible, not to achieve as much pleasure as possible.

Negative utilitarianism and motivation

I don’t see negative utilitarianism as a metaphysical property of the universe, but as a coyuntural consequence of how brains are (metaphorically), in general, “designed” by evolution, evolution as we know it.

A consequence of negative utilitarianism, a theory in which I believe, is that individuals can only be motivated, basically, by negative experiences (like fear, pain, suffering…), even if they feel and believe that they are motivated by positive experiences (like love, pleasure or admiration…) [Please help me to find counterexamples. Vanity? Would it work without the pain of being ignored?]

Of course, this will happen until we modify the inconsiderate “programming” of nature. I don’t see why we can’t configure brains to be motivated by gradients of bliss. As it’s proposed by David Pearce at The Hedonistic Imperative.

When the time comes to motivate your team, of course, even if suffering is the only way in which, basically, motivation works, this does not mean that the more suffering, the better (more motivation). This is not how it works.

Negative utilitarianism considers that the fact that the experiences are more or less positive have little or no relevance. This can be misunderstood as the idea that according to negative utilitarianism, having positive experiences is not relevant. It is just the opposite! What negative utilitarianism defends is that the most relevant of all, the only relevant in the end, is not having negative experiences. And for a being who has experiences, the only way to have no negative experiences is having just neutral or positive experiences.

Therefore, for negative utilitarianism, having positive experiences is absolutely relevant; What is not relevant is that the positive experiences are as positive as possible: it is enough that they are not negative. That is, according to negative utilitarianism, positive experiences are relevant because they are not negative, and consequently, the motivation for positive experiences is actually a motivation for not having negative experiences.

If we assume that negative utilitarianism is true, I think that the only way to really motivate is through negative experiences. Why? Fundamentally, because if the negative utilitarianism is true, every time we are motivated to achieve a positive experience, what really motivates us is to avoid the negative experience. Some examples:

- We do not eat for pleasure, but basically to avoid the discomfort of hunger.

- We are not looking for a partner for being happy together, but basically for not being sad and lonely.

This is not very intuitive. Don’t we prefer food as delicious as possible? Don’t we want to share our life with a person as wonderful as possible? These apparent counterexamples are solved if we approach the issue globally, taking into account all the details.

It is important to remember that in negative utilitarianism, positive and negative experiences are not added and compensated, and that what is relevant according to negative utilitarianism is not having any negative experience of absolutely any kind.

We can consider that the overall balance of the well-being of a sentient being is composed of a set of multitude of variables, related for example with temperature, mood, hunger, physical pain, etc. According to negative utilitarianism, when an individual is satisfied in absolutely all possible variables, then it will not be relevant for this individual to increase the value of any of them. And it will be enough that only one of these variables exceeds a certain threshold so that it becomes the priority.

Of course, there will be variables for which it will be very difficult or impossible to affect its value. For example, who has had an irreversible loss can turn to professional success, the admiration of others, or the enjoyment of exotic and delicious foods and drinks, as exotic and delicious as possible, as a way to relieve suffering of that loss.

For negative utilitarianism, happiness consists in not having suffering. Of course everyone wants a house the more beautiful and comfortable the better, and wants to have a partner the more attractive and loving the better. But once someone is satisfied, not only with his house and his partner, but with his body, with his work, with absolutely everything; When everything is absolutely fine, when nothing is wrong, in all possible dimensions, then it is no longer relevant to further improve what is already ok. At least, this is the interpretation of negative utilitarianism.

Assuming that negative utilitarianism is true, if we have the feeling that we are motivated to achieve positive experiences, what really happens is that we are motivated to avoid negative experiences. We are not motivated by positive experiences by themselves, but only by the fact that they are not negative.

Is this the whole truth? If we still feel that we are motivated to achieve positive experiences, as positive as possible, there still may be several cases:

- It is an illusion. We believe that we are motivated to achieve positive experiences but really all we do is try to avoid the negative ones.

- We are motivated to achieve as positive experiences as possible in a given variable, but this is really a substitute that is masking the real motivation, which is to avoid negative experience in another variable (or in another aspect of the same variable).

Indeed, assuming that negative utilitarianism is true, it is not literally true that we cannot motivate someone through positive experiences, as positive as possible, in the sense that the promise of positive experience, as positive as possible, can motivate someone to do something. But negative utilitarianism explains this situation through the existence of suffering in the same or another variable that is what really produces the motivation. Without that suffering, only the promise of even more positive experience would not work. So, ultimately, if the negative utilitarianism is true, if the only relevant thing is suffering, then the only way to motivate someone is through the existence of suffering.

Specifying examples of this idea in the matter of motivation, for example in a work environment:

- You can motivate a collaborator with more money, but you can do that while they need the money to relieve frustration. You cannot motivate with more money someone who is at peace and happy in every possible dimension.

- You can motivate a collaborator with compliments and recognition, but you can do that only as long as that individual feels the fear of rejection and the need to feel accepted and loved. You cannot motivate with more praise and recognition someone who is already at peace, happy and satisfied.

- You can motivate a collaborator with your unconditional friendship, but you can do that as long as that individual feels the loneliness and existential emptiness of feeling separated from the rest of the universe, hated or despised by others, or at least at risk of this happening. You cannot motivate with more attention someone who already feels one with everything with the universe, loved and loved by all, hated by no one.

Negative utilitarianism in the frame of ethical theories

Within the study and development of ethics we can distinguish several fields. At least, the following:

- Descriptive ethics (or “comparative ethics”), is the study of people’s beliefs about morality. It tries to answer the question: What do people think is right?

- Prescriptive ethics (or “normative ethics”), is the study of ethical theories in the aspect of prescribing how people ought to act. It tries to answer the question: How should people act?

- Meta-ethics is the study of ethics itself. Meta-ethics and Axiology tries to answer questions like: What does “right” even mean? What is good? What is better? What is valuable?

In ethics there are three major currents of thought or types of theories, which are:

- Deontology (or “deontological ethics” or “deontologism”)

- Consequentialism (within which utilitarianism stands out, although there are other types of consequentialism such as eg egoism and altruism)

- Ethics of character, in which highlights the virtue ethics (post-aristotelian ethics), although there are other ethics related to character, such as the ethics of honor, of chivalry or of heroism.

Negative utilitarianism is a defined as a “form of negative consequentialism that can be described as the view that we should minimize the total amount of aggregate suffering, or that we should minimize suffering and then, secondarily, maximize the total amount of happiness. It can be considered as a version of utilitarianism that gives greater priority to reducing suffering (negative utility or ‘disutility’) than to increasing pleasure (positive utility)”.

Types of consequentialism:

- Classic utilitarianism (or simply “utilitarianism”)

- Negative utilitarianism

- Positive utilitarianism

- Prioritarianism

- Selfishness

- Altruism

- Egalitarianism

Types of utilitarianism (which are not in the previous list):

- Negative total utilitarianism, that tolerates suffering that can be compensated within the same person

- Negative preference utilitarianism, that avoids the problem of moral killing with reference to existing preferences that such killing would violate, while it still demands a justification for the creation of new lives.

- Motive utilitarianism

Types of negative utilitarianism (which are not in the previous list):

- Classic Negative utilitarianism (or simply “Negative utilitarianism”)

- Weak negative utilitarianism (also called negative-leaning utilitarianism)

Prioritarianism has much in common with negative utilitarianism, I even think it could be considered as a kind of utilitarianism. However, it is considered a type of consequentialism. On the other hand, negative utilitarianism is usually considered as a type of utilitarianism, with negative utilitarianism and “utilitarianism” (classical utilitarianism) so different.

We can ask ourselves the following questions: Is negative utilitarianism really a type of utilitarianism? Negative utilitarianism is so far from classical utilitarianism (or “utilitarianism”) that it is best understood as a type of consequentialism, and not as a type of utilitarianism. Is negative utilitarianism a good name for negative utilitarianism? Is, in fact, utilitarianism a good name for utilitarianism?

As an alternative to the word “utilitarianism” it has been proposed, for example felicitarianism (or felicitism).

As an alternative to the expression “negative utilitarianism”, and without meaning the same, we speak about Suffering Focused Ethics (SFE), a broader term:

“Suffering-focused ethics is an all-encompassing term for moral views that prioritise the the alleviation and prevention of suffering. It includes normative ethical theories such as negative utilitarianism, in addition to views on axiology and population ethics which give special weight to suffering” [4].

Depending on the definition or interpretation we make of the idea of “suffering”, some types of utilitarianism can converge to be almost the same, or even exactly the same.

“Given that happiness and suffering aren’t quantities whose meanings everyone agrees upon, it becomes unclear what the difference is between negative and non-negative forms of utilitarianism. A person who is considered by others to be a negative utilitarian may just feel that he’s a regular utilitarian who uses a definition of suffering according to which suffering is vastly more intense than most people assume. In light of this problem, I think the best way to define “negative utilitarian” is just “someone who gives (much) more weight to suffering than most other utilitarians do when evaluating situations”. For instance, in a world where most people only gave moral weight to happiness, Jeremy Bentham would be a (weak) negative utilitarian” [5].

Other definitions:

“Suffering-focused ethics is an umbrella term for moral views that place primary or particular importance on the prevention of suffering. Most views that fall into this category are pluralistic in that they hold that other things besides reducing suffering also matter morally. […] Not all of these intuitions may ring true or appeal to everyone, but each of them can ground concern for suffering as a moral priority.”

Lukas Gloor, “The Case for Suffering-Focused Ethics”

https://foundational-research.org/the-case-for-suffering-focused-ethics/

“Ethical negative-utilitarianism is a value system which challenges the moral symmetry of pleasure and pain. It doesn’t deny the value of increasing the happiness of the already happy. Yet it attaches value in a distinctively moral sense of the term only to actions which tend to minimize or eliminate suffering. It is counter-intuitive, not least insofar as the doctrine entails that from a purely ethical perspective it wouldn’t matter if nothing at all had existed or everything ceased to exist. No inherent moral value is attached to pleasure or pleasant states.”

David Pearce, “The Hedonistic Imperative”

https://www.hedweb.com/

“Negative utilitarian”: an unfortunate name?

As Jiwoon Hwang and others have pointed out, the ‘negative’ in ‘negative utilitarianism’ is quite likely to sound quite negatively (in a sense of ‘bad’, ‘pessimistic’) to most people. In early 2015, Brian Tomasik started to use the expression “Suffering-Focused Ethics”, initially as a random combination of words, and soon the people at FRI began using it as well. In summer 2015, they explicitly decided to start using the terminology systematically.

Brian Tomasik, “Reasons to Promote Suffering-Focused Ethics”

https://reducing-suffering.org/the-case-for-promoting-suffering-focused-ethics/

Footnotes / related resources

[1] See also Tranquilism by Lukas Gloor and Tranquilism (search) on Magnus Vinding‘s

[2] http://www.preventsuffering.org/#about-opis

[3] http://www.jonathanleighton.org/compassionatesystemdesign/ethicalprinciples

[4] https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Suffering-focused_ethics

[5] https://reducing-suffering.org/net-suffering-nature-reply-michael-plant/

Acknowledgments

8 Comments