“The little I know I owe to my ignorance” –Plato

I will give the name Sentience Platonism to the idea that experiences exist by themselves, regardless of the sentient beings who experience them. Even if the probability of Sentience Platonism were extremely small, while there is a higher than zero probability, and considering that is not very clear where sentience comes from, we might think twice before disregarding this idea, because should it be true, its implications for preventing suffering would be immense.

Contents

- Introduction to Platonism

- Critique of Platonism

- Pseudoplatonism

- Metaphores in science and philosophy

- Sentience Platonism

- Definition

- Emergentist monism versus immersionist monism of sentience

- Implications in the prevention of suffering

- Conclusions

- Acknowledgements

Introduction to Platonism

The philosopher known as Plato (Aristocles) lived from 427 BC to 347 BC. He was a student of Socrates and teacher of Aristotle. The adjective Platonic is usually used to refer to the existence of universals or ideals. For example, appleness and redness are universals of a specific red apple.

Platonism is considered an ontological dualism which proposes the existence of two kinds of reality:

- a sensible world [1] (the world of things perceived by the senses, in which the individual realities, materials, which happen in time and space, such as an apple, are found) and

- a world of ideas (the world of things known through reason, where the immutable, eternal, invisible, intangible, independent of time and space realities, such as the idea of apple, are found).

Platonism underlines the existence of this second world independently of the first, and even proposes that the second world is the cause or generator of the first.

Critique of Platonism

Platonism proposes that the ideal world produces the things of the material world, but it may well be the opposite situation: our experiences with tables, apples, loves or homelands are forging our mental concept (ideal) of “table”, “apple”, ” love” and “homeland”.

Platonism may seem an unnecessary complication, as well as being unintuitive. It seems reasonable to think that the things which we perceive exist without being inherited from some ideal. It is true that apples follow a pattern, which we can call the “ideal apple”, but what evidence or clues do we have of the independent existence of that ideal? And why should the existence of a specific apple depend on the existence of the Platonic ideal of apple?

Platonism seems still stranger when referring to other ideas, such as numbers. Suppose we have 42 tables and 42 apples. Should this make us assume the existence of the Platonic ideal of the number 42 with the independent existence of the 42 tables and 42 apples? If the Platonic ideal of the number 42 were to disappear, would we cease to have 42 tables and 42 apples? How many would we have then? 41+x tables and 41+x apples (x being an “unknown” number)? How can this be possible?

Pseudoplatonism

Even if we think that strict Platonism is something outrageous and unjustified, we must recognise that in the world there are things which are very similar to each other and that it does not seem unreasonable to think that somehow they have been made “from the same mould”. If we interpret Platonism softly, as the existence of a special kind of unique things that determine and cause a multitude of other special kinds of things, we can find positive answers to the above questions.

Not all apples are so similar to each other. They come in different sizes, shapes and colours (red, green and yellow). But the apples from the same tree certainly are very similar to each other. They all have the same colour and shape. We know why: they have the same DNA. A DNA molecule is like a set of instructions, like a computer program, and contains somehow the “idea” of everything that this program can generate: cells, organs, flowers, apples…

Of course, both apples and DNA molecules are composed of the same type of elements: atoms (or whatever other lower particles we want to use to describe them). It is not necessary to invoke a world of ideals foreign to the material world to explain the existence of apples. We know how living objects, such as apples, are generated from DNA molecules. Furthermore, both apples and DNA molecules belong to the set of things created by combining atoms (and in that sense, they belong to the same “world”). We cannot honestly claim that the similarity between apples comes from an apple ideal. As we have said, both elements (DNA molecules and apples) belong to the same type of things (things created with atoms) and from that point of view they do not belong to “different worlds” whose existence Platonism requires. But we must recognize that something similar happens, not a strict Platonism, but a kind of pseudo-Platonism in which the Platonic world of the DNA of the apple tree generates the world of the apples which share in some way that genetic ideal. (Of course, the atoms in turn could share an ideal, having a Platonic origin.)

Could something similar happen with numbers?

Trenaren txistu adarrak isilarazi du Onofre. Tunelean sartu da laster ketsua suge. Burdinetan hamaika hanka baldarren hotsa errepikatu da.

[The train whistle silences Onofre. The steaming snake quickly enters the tunnel. In irons rattles the sound of thousands of clumsy feet.]

Azken fusila. Edorta Jimenez.

Perhaps because they speak with difficulty, children two or three years old tend to respond with fingers to questions about their age. Adults also occasionally use fingers to communicate numbers. Every time someone produces the symbol 9 with their fingers it conveys the idea of 9. We can use our hands to transmit 9 as often as we like: 9 sheep, 9 stones, 9 shouts… But if we lose two fingers in an accident, we can no longer transmit the number 9 with our hands. In fact, the number 10 is a limit, and numbers from 11 onwards can be considered “many.” So it is exactly in the Basque language, in which the word “hamaika” (literally, eleven) is translated into English as “thousands” (meaning in both cases: “many”). A child may appear on television and if asked about his age, his fingers may serve to convey the idea of “three” to millions of people, activating it in their brains.

Contrary to what was mentioned earlier in this text, for some, platonism in mathematics can be very intuitive and difficult to reject. The numbers in the infinite series of natural numbers (1, 2, 3, 4…) seem to have some sort of timeless and independent platonic existence. Arbitrarily large natural numbers which no one has ever thought of and no one has ever represented (written, spoken…) seem to have some kind of eternal, unchanging self-existence. Natural numbers seem to be in an ideal place, always available to be invoked or discovered, but not invented.

If it does not seem impossible to have some kind of platonism in numbers why not propose a possible platonism of experiences?

The different perceptions we have (and particularly, the visual ones) converge towards a specific, objective material external world where water weighs more than oil. Curiously, something similar happens with platonic ideas, such as mathematics, which also converge towards a set of certain truths, where the length of a circumference is equal to the diameter multiplied by a curious number that we call Pi. If it is the convergence of subjective experiences that gives credibility to the physical world, should not the convergence of mathematical ideas give credence to the platonic world of mathematics? Many people agree on the first point, very intuitive (convergence of subjective experiences gives credibility to the physical world), many less with the second point (convergence of mathematical ideas gives credibility to the platonic world of mathematics). I further propose a third: that the convergence of subjective experiences gives credibility to a possible platonic world of experiences.

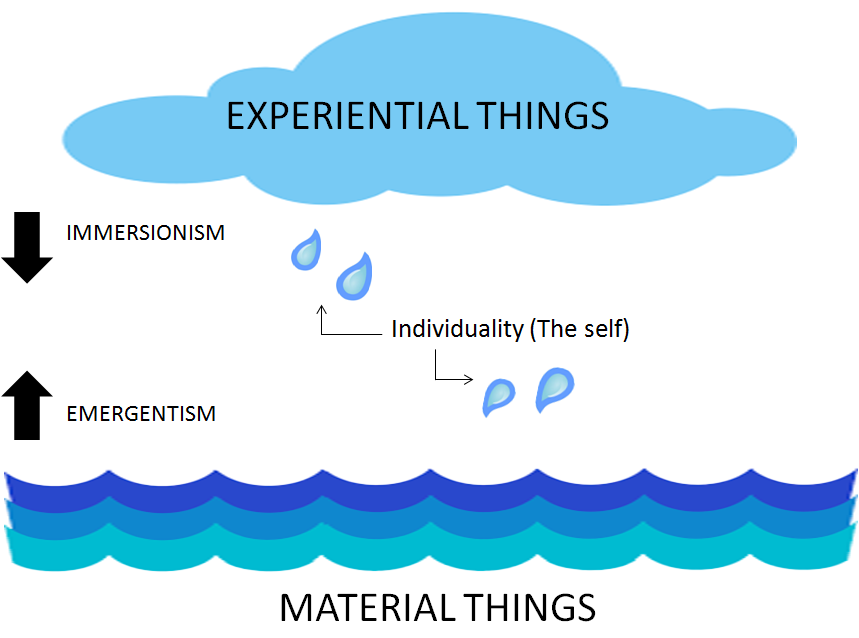

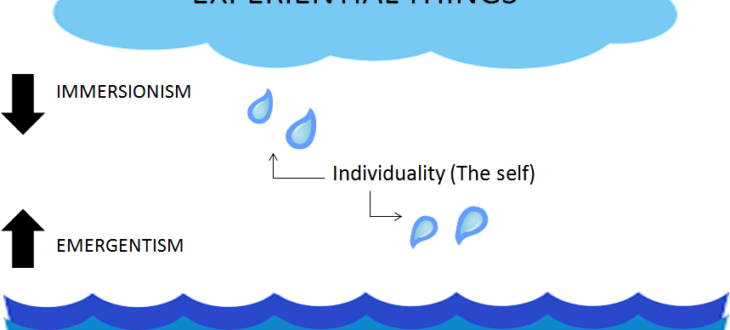

There is a symmetry between emergentism and immersionism. Emergentism and immersionism are two symmetrical metaphysical approaches to describe reality.

In the emergentist approach “material things” (materials), grouped in a certain way, generate individuality (the self). Additionally, the individual experiences the existence of “experiential things”, such as the feeling of cold or love, but this “experiential reality” is considered an epiphenomenon or even denied (eliminativism).

In the immersionist approach, “experiential things” (experiences), ungrouped in a certain way, generate individuality (the self). Additionally, the individual experiences the existence of “material things”, such as a gold atom or a planet, but this “material reality” is considered an epiphenomenon or even denied (spiritualism).

The hypothesis of the existence of experiences, independently of the individuals who experience them, is analogous and symmetrical to the hypothesis of the existence of the materials, independently of the individuals who experience them.

It does not seem entirely unreasonable to think that if somehow the experiences of concrete beings depended on certain platonic experiences, then modifying or even eliminating the platonic experience could alleviate certain negative experiences for all beings or even cause them to disappear altogether.

Sentience Platonism can be reinforced by the idea that perhaps we live in a simulation and beings may be “instantiated” from an ideal object, in the same way as “instances” of software objects in “Object-Oriented Programming“. For example, we could store the variable “happiness” of our software agents in a hardware binary system with 4 bits, 0000 being the lowest value and 1111 the highest value. Changing the system so we use three bits instead of four, it might seem that automatically we would be able to do away with certain kinds of experiences. However, this does not seem to make much sense when we talk about sentience, because the fact of assigning the name “happiness” to a computer variable does not give us any guarantee that the software object that contains it experiences happiness depending on its value. Quite on the contrary, emergentist monism is perfectly compatible with the idea that what we consider the material world is a simulation, and sentience can emerge both in our “material” world and in the worlds that we simulate. This interpretation of the simulation argument approaches the notion that all matter is information (particles are waves, fields), but there is another way to see the simulation argument and it is to consider that only experiences are simulated (created from the other world). Certainly, it is not necessary to simulate the entire physical universe, but only the tangible universe (those parts that someone will perceive). That is, in fact, it is not necessary to simulate absolutely anything material in the universe; it is only necessary to simulate the subjective experiences. And this way of viewing the simulation argument seem to be more conducive to Sentience Platonism, because in the same way that we think that we use matter (computers) to simulate matter (aircraft and bridges), perhaps in another platonic world someone is using sentience to simulate sentience.

An objection that may appear at this point is that even being true, this hypothesis is useless because simulations, and in general, beings created by other beings will always be lower and weaker than their creators. But this is not true. The simulations could interact with their creators. At some point, artificial general intelligence could be more powerful and flexible than the most powerful and flexible minds known to date: human minds. The simulated worlds could be more powerful than their creators, and eventually modify and control their creators.

Metaphores in science and philosophy

“Who knows! Perhaps sounds behave similarly to the waves on the water. I mean that if you throw a stone into a pond, you will see concentric circles expanding. And if you connect two ponds even through a small channel of water, you can see how waves pass through it and extend back to the other side. Maybe something similar happens with sound, although we do not see the waves”.

Platonism has been criticised since Aristotle himself for being explained by metaphors that do not prove anything. Effectively, metaphors have explanatory power, but not demonstrative.

I do not claim that metaphors appearing in this text are considered as proofs or as evidence of certain assumptions. Their intention is to provide teaching capacity and credibility, stressing that while there are certain assumptions that we might consider unlikely, we might not be in a condition to establish that they are totally impossible; and if they are true, the consequences could be colossal. These two arguments (1: it is possible; and 2: the consequences would be very relevant) may not be sufficient to consider crackpot hypotheses in relation to those matters that we believe we understand well, but we could give them a try if the assumptions were about some of the things that we still do not fully understand well, as reflected in the names we give to “the problem of consciousness“, “the hard problem of consciousness” and “the mind-body problem“.

Sentience Platonism

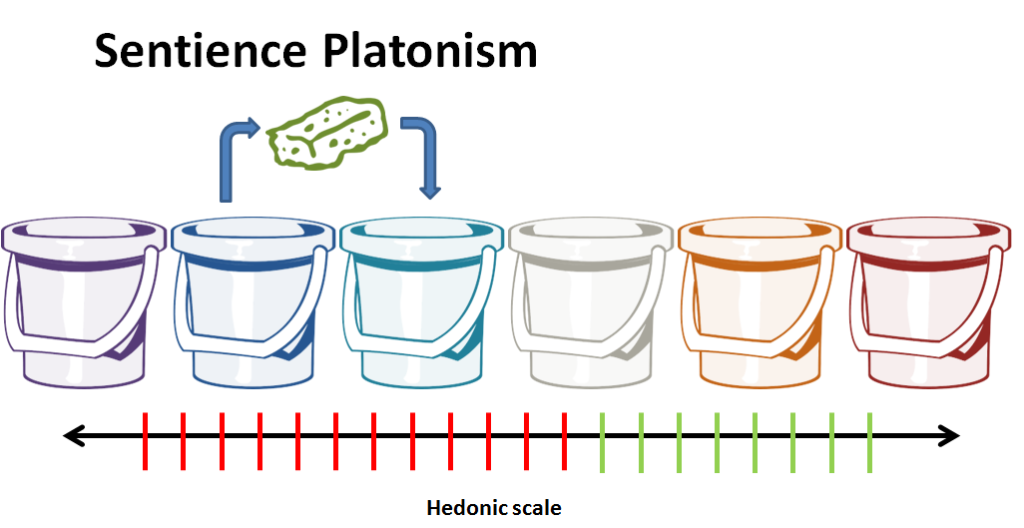

Suppose we have several buckets of water with different temperatures. Imagine that there are some plastic sponges going into and coming out of the buckets.

In this metaphor wet sponges are sentient beings, and buckets of water (at different temperatures) are the experiences. Each sponge along with the water therein forms a coherent whole, in which the colour of the water within the sponge is identified as the specific experience that the sponge is experiencing.

High temperatures correspond to positive experiences (different satisfactions or pleasures) and low temperatures with negative experiences (different frustrations or pains). In each sponge, the higher the temperature, the more pleasant the feeling will be, and the lower, the more painful; there being an intermediate temperature at which a state of indifference occurs without significant pain or pleasure.

Obviously, there are different experiences (waters), both positive and negative (hot or cold), which we could evaluate in the same way (same temperature), although of a different kind. For example, if I want to dedicate this weekend to visiting old friends, maybe I could travel to Valencia to see a friend, or I could also go to Malaga to see another. If I have doubts and do not know which of the two trips to choose, perhaps it is because both experiences, even though different, will provide me a similar satisfaction. To account for this we can assume that the buckets have coloured water, so that two buckets can have water at the same temperature, but of a different colour. In the metaphor the two weekends would be like two buckets with water of different colours, but the same temperature.

It is very important to note that in this metaphor water represents experiences, and these experiences (water) exist independently of the sponges. For example, a bucket labelled “toothache” may contain blue water at 4 degrees Celsius, and another labelled “pleasant tickles” may contain orange water at 27 degrees Celsius. By putting the sponge in a bucket, the sponge acquires this experience (toothache or tickling) and sponges (beings) can identify their own experiences and those of other beings depending on the type of water they contain. But the water exists independently of the sponges.

The sponges go into and out of the buckets. By changing bucket, the sponge takes on different water, in the same way that beings experience different things over time. In a project to reduce or eliminate suffering, and according to this metaphor, there is a risk that we could be focused on alleviating suffering by carrying sponges progressively from the coldest buckets to the hottest buckets. And assuming that a majority of buckets of cold water exists, and that sponges are able to reproduce, we could devote ourselves to promoting avoiding the reproduction of sponges, as a way to avoid having new sponges in buckets of cold water. We could even suggest that the best possible world is one in which there are no sponges.

Indeed, in both cases we could check that there are individual and very specific sponges that have improved their welfare, and are now in warmer buckets. Or that there are now no sponges in particularly cold buckets. The problem is that these buckets of cold water would still exist, and if the metaphor were true, we would not have really solved anything. If this metaphor really did represent the nature of experiences, we would be wasting time carrying sponges from some buckets to others or preventing sponges from reproducing. What we should do is raise the temperature of the cold buckets. On doing so, certain negative experiences would cease to exist, or would be relieved instantly, for all, and forever.

Sentience Platonism is compatible with the idea coined as “Open Individualism” that is, that there is only a single subjective identity that is everyone at once.

Definition

Sentience Platonism is the idea that experiences exist by themselves, regardless of the sentient beings who experience them. How can that be possible? Our minds could be like radio receivers capable of connecting some “station”. The mind, as the radio-receiver, does not generate anything new, but connects to something that preexists.

That is, all the possible ingredients or aspects of all the types of experience that we know exist permanently in a certain Platonic world, as if they were radio stations. The mind, according to its state, is connected to a different combination of emitters of experiences. The mind does not generate the experience, but connects to it.

Emergentist monism versus immersionist monism of sentience

The idea that sentience emerges without anything further under certain conditions or configurations, and that this is nothing special, can be very intuitive and can be supported in some metaphors, encouraging us to think that Sentience Platonism is false.

In his book “The Society of Mind” Marvin Minsky wondered: What is the concept of “container”? And how do boxes manage to keep things inside? We can put together six boards creating the shape of a geometric cube, which will acquire as a result the property of “containing things.” It will thus become a container. We can say that the property of being a “container” emerges from some configuration or interaction between various elements.

Sentience, like the ability to be a “container”, could be gradual. With the help of the force of gravity, which attracts things “down”, and having five flat surfaces, we can make a pretty good container. Even with three it can work if we hold it well in our hands. There is no need to evoke any strange Platonic world to explain and understand containers.

Metaphors like that of a box might lead us to think that we understand sentience. Marvin Minsky among others proposes that sentience occurs in the interaction of different mental agents in a “market” in which they compete and solutions are chosen to different needs that can be contradictory, such as: being sleepy and hungry at the same time. Sentience is related to or identified with the existence of a subjective and egocentric neuronal representation of the environment.

It is said that sentience emerges from certain configurations or its existence is useful evolutionarily. But in the same way that I used the metaphor of being a “container” to explain and defend emergentist monism, now I will use the metaphor of flight to defend and explain why a immersionist monism is possible: the Sentience Platonism.

We can define “flying” as “falling and missing the ground“. Planning is a certain kind of flying and evolutionarily it may have been extremely useful to have rudimentary wings which serve to brake and steer the fall as well as possible, until the complex flight mechanisms we can see in a majestic condor are developed.

The ability to feel could be like the ability to fly. However, we could be wrongly defining the ability to feel as the ability to have feathers.

It is not enough to say that sentience is useful for survival. Wings are also useful for flight, but you can have wings and not fly, and fly and not have wings. You may have artificial feathers which are not created to fly, but to write; and one can also fly by plane, without feathers. If we only look at the “wings” of sentience, maybe we are leaving out a lot of sentience in the physical world which we are not able to recognise. David Chalmers suggests that even a thermostat might have experiences.

When we explain how to recognise another sentient being, we speak of behavioural, developmental and physiological criteria, but we do this “a posteriori” in a very egocentric manner. Based on the maximum evidence “I feel”, it seems we interpolate between individuals who have similar appearance and/or behaviour to ours (“If it looks like me and behaves like me, it will feel like me”); it also seems that we interpolate between species (“If it has been created like me, it will feel like me”) assessing whether it has the same origin (evolutionary) and if it is genetically close to me. Additionally and since sentience has an evolutionary utility, it seems that we establish – unjustifiedly – that having an evolutionary utility is necessary for sentience to exist.

If we were to look at a group of humans killing a pig in order to eat it, we could try to defend the pig arguing that the animal feels: “look at the panicked expression in its eyes”, “listen to its heart-rending cries”, “see how it writhes in pain”… but this could be like saying, in order to argue that an animal can fly, “see how light its bones are”, “what an aerodynamic shape” and “what majestic wings”. The fact that that description fits that of a flying creature does not mean that all flying beings should have those attributes. Planes are aerodynamic but do not have feathers and are not especially light.

In Platonism, the world of ideas is considered the real, genuine and perfect, while tangible world is an imperfect representation of the first, which reality is not as strong. In the metaphor of sponges and buckets of water, and in terms of sentience, there is only one sentience, water, so I consider this Sentience Platonism more monistic than dualistic, and I prefer to call it a immersionist monism. This reminds metaphors of Sufism about the drop and the sea:

“Drop the shape, break the form | The shape of mind | The form of this dream of existence. Listen to the ocean | The true song of creation | That there was ocean and nothing else | And now there is ocean and nothing else”.

Sentience seems to emerge under certain conditions, but precisely what we do is to look for it in conditions similar to oneself, oneself being sentient. The problem of sentience is not well resolved and the immersionist monism of Sentience Platonism should not be ruled out, especially when the consequences in respect of reducing suffering would be overwhelming.

Implications in the prevention of suffering

In Sentience Platonism we can consider at least three possibilities. In all three cases I am going to talk about a platonic experience that generates in some way several conventional experiences and I will analyze, assuming that this hypothesis was true, what would be its consequences in terms of relief and prevention of suffering.

- The first hypothesis is that a single Platonic experience can generate multiple independent conventional experiences, which exist by themselves, disconnected from the Platonic experience that generated them, in the same way that a cookie-making mold (equivalent to the Platonic experience) can make countless individual cookies (equivalent to multiple conventional experiences), with a complete disconnection of each cookie with respect to the mold once generated, because even if we destroy the mold, the cookies generated by the mold will continue to exist.

- A second possibility is that the Platonic experience generates multiple experiences that are totally dependent for being permanently “connected” to the Platonic experience, in the same way that a radio station that emits a happy song (equivalent to the Platonic experience) can emit towards an infinity of individual radio receivers (equivalent to multiple conventional experiences). If we turn off the station, instantaneously all the radio receivers will stop playing that signal.

- Finally, there is another possibility, which is that all the experiences produced from the Platonic experience of a certain type are ultimately the same experience, essentially the same, the same thing, as happens for example when a deal is closed, as a loan or a purchase agreement. Once an agreement has been reached (equivalent to the Platonic experience) we can reflect it in several documents (equivalent to multiple conventional experiences). A single agreement can be mentioned in several documents, and of each one of the documents that reflect agreements or contracts, several copies are usually made, but the agreement is unique. All copies of a contract are really the same thing. Destroying one of them will not eliminate the agreement. Not even eliminating all copies of a contract will eliminate that agreement, we will only eliminate documentary evidence of that agreement. On the other hand, if we reach a new agreement that cancels the previous one, immediately all the documentary copies will be invalid.

The implications of each modality of Sentience Platonism in the alleviation and prevention of suffering are the following

- “Cookie mold”. By eliminating a “cookie mold” from a negative experience we can avoid generating this negative experience in the future. But in order to help the beings that currently experience negative experiences, which have previously been generated by this “mold”, we must work to help these beings, one by one. This type of Sentience Platonism recalls a situation that is not metaphorical but real: genetic patterns are a kind of “cookie mold” that generates beings and therefore experiences of a certain type. By controlling and modifying genetic patterns we could avoid suffering in the future, as proposed by David Pearce.

- “Radio transmitter”. In this case, turning off the radio station that generates the negative experience will avoid this negative experience in all beings. The great advantage is that if we can access the station, it will not be necessary to intervene helping individual beings one by one. Simply turn off the station (or change the song it emits) and the effect will be immediate, in all beings.

- “Sales agreement”. The implications of this type of Sentience Platonism are overwhelming. This would imply that the total sentience of the universe remains constant, and that by helping an individual being who has a negative experience we would not be essentially doing anything, we would only do it apparently. If this hypothesis were true, the only effective way to alleviate suffering would be to eliminate or modify the Platonic ideal of such suffering (in the metaphor, reaching a new agreement that cancels the previous one). Instead, in an optimistic sense, if there were any way to eliminate the suffering of the past it would be under a paradigm like this. To eliminate the suffering of the past could start to sound not so extravagant if we consider the possibility of eternalism.

Reducing the suffering of the past is a little less implausible that it sounds. Under Eternalism, past experiencies are as real as present experiences. The bad news is that under this approach, past suffering experiences are real, like if they were happening now. The good news is that if they are real, we can act on them.

Conclusions

Emergentist monism seems a good explanation of the emergence of sentience but we should not rule out other more or less Platonic possibilities, analogous to the Platonic existence of natural numbers or the metaphor of sponges and buckets of water at different temperatures, in which sponges are beings, the waters being experiences. I do not claim that the metaphor of sponges encourages one to stop being compassionate to specific individual beings. On the contrary, I think we should help the maximum number of individuals that we can help, giving priority to altruism with those who are in the most difficult and desperate situations, avoiding as far as possible the reproduction of sentient living beings when there is no guarantee of the happiness of the descendants, and trying to find the most effective ways to help the maximum number of sentient beings, employing the best scientific knowledge and technological tools that we have, and as David Pearce proposes, using genetic engineering to improve the programming which Nature has given us, sentient beings. And just as we should not hastily dismiss sentience in less intuitive settings, such as the sentience of insects and the sentience of simulations, which could generate a moral catastrophe, we should also consider the possibility of Sentience Platonism.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Janique Behman and Vicent Castellar for the very useful suggestions received after reading the first draft of this article.

About the document

- First written: 28 Sep. 2016

- Updated: 23 Mar 2017

- Updated: 3 Apr 2018

- Last updated: 1 Apr 2024

Other versions of this document

- Published at Academia: https://www.academia.edu/30182614/Sentience_Platonism

- PDF version

Notes

- [1] With the expression “sensible world”, Plato does not refer (in principle) to the world of subjective experiences, the world of the senses, the world of sensations, the world of perceptions, the world of emotions, etc but to the outside world, to the objective world, to the material world, to the world whose existence -now yes- we know from subjective experiences, such as sensations or perceptions. It seems that we are missing a third world and we have to fit it in somewhere. Will this world of subjective experiences be included in that of ideas? That is precisely what I am trying to argue.

My brain is only a receiver, in the Universe there is a core from which we obtain knowledge, strength and inspiration. I have not penetrated into the secrets of this core, but I know that it exists.

Nikola Tesla